SILENCE IS ONE OF THE HARDEST

ARGUMENTS TO REFUTE

What are arguments?

An

argument is a series of statements, called the premises or premises (both

spellings are acceptable), and intended to determine the degree of truth of

another statement, the conclusion.

An

argument is a rationale in which the reason presents evidence in support of a claim

made in the conclusion. An explanation

is a rationale in which the reason presents a cause of some fact represented by

the conclusion. Its purpose is to help us understand how or why that fact

occurs.

uses of arguments

Making and assessing arguments can help us

get closer to understanding the truth. At the very least, the process helps

make us aware of our reasons for believing what we believe, and it enables us

to use reason when we discuss our beliefs with other people.

- Inquiry

- to form opinions

- to question opinions

- to reason our way through conflicts or contradictions

- Conviction

- Arguing to inquire centers on asking questions: we want to expose and examine what we think.

- Arguing to convince requires us to make a case, to get others to agree with what we think. While inquiry is a cooperative use of argument, convincing is competitive. We put our case against the case of others in an effort to win the assent of readers.

- Persuasion

- In general, the more academic the audience or the more purely intellectual the issue, the more likely that the writing task involves an argument to convince rather than to persuade. In most philosophy or science assignments, for example, the writer would usually focus on conviction rather than persuasion, confining the argument primarily to thesis, reasons, and evidence. But when you are working with public issues, with matters of policy or questions of right and wrong, persuasion’s fuller range of appeal is usually appropriate.

- Persuasion begins with difference and, when it works, ends with identity. We expect that before reading our argument, readers will differ from us in beliefs, attitudes, and/or desires. A successful persuasive argument brings readers and writer together, creating a sense of connection between parties.

- Negotiation

- Each side must listen closely to understand the other side’s case and the emotional commitments and values that support that case. The aim of negotiation is to build consensus, usually by making and asking for concessions. Dialogue plays a key role, bringing us full circle back to argument as inquiry. Negotiation often depends on collaborative problem-solving.

The uses of argument by Stephen e. toulmin

Types of Arguments

There are three basic structures or types of argument you

are likely to encounter in college: the Toulmin argument, the Rogerian

argument, and the Classical or Aristotelian argument. Although the Toulmin

method was originally developed to analyze arguments, some professors will ask

you to model its components. Each of these serves a different purpose, and

deciding which type to use depends upon the rhetorical situation: In other

words, you have to think about what is going to work best for your audience

given your topic and the situation in which you are writing.

There are several kinds of arguments in logic, the

best-known of which are "deductive" and "inductive." An

argument has one or more premises but only one conclusion.

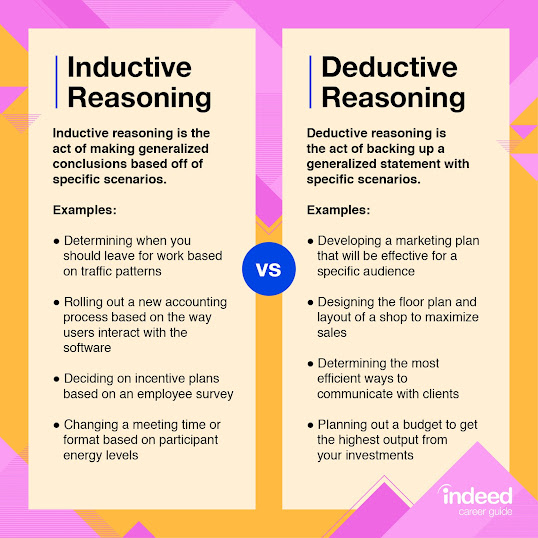

Deductive arguments and Inductive arguments

If the argumenter believes that the truth of the premises definitely establishes the truth of the conclusion, then the argument is deductive. If the arguer believes that the truth of the premises provides only good reasons to believe the conclusion is probably true, then the argument is inductive.

Inductive argument is the act of making generalizeed conclution based off of specific scenarios.Deductive argument is the act of backing up a generalized statement with specific scenarios.

Justification

Justification is something that proves, explains or

supports.

An example of justification is an employer bringing evidence

to support why they fired an employee. A reason, explanation, or excuse which

provides convincing, morally acceptable support for behavior or for a belief or

occurrence.

What are Arguments Used For? Justification

Explanation

Philosophy, like several different studies, targets by and

large at understanding.

An argument is a rationale in which the reason presents

evidence in support of a claim made in the conclusion. ... An explanation is a

rationale in which the reason presents a cause of some fact represented by the

conclusion. Its purpose is to help us understand how or why that fact occurs.

Explanation, in philosophy, set of statements that makes intelligible the existence or occurrence of an object, event, or state of affairs.

The langauge of arguments

Argument helps us learn to clarify our thoughts and

articulate them honestly and accurately and to consider the ideas of others in

a respectful and critical manner. The purpose of argument is to change people's

points of view or to persuade people to a particular action or behavior.

Language, a system of conventional spoken, manual (signed), or written symbols by means of which human beings, as members of a social group and participants in its culture, express themselves.

Dinesh Shiwantha Wanigathunga

dineshshiwantha@gmail.com

No comments:

Post a Comment