If you want a testimony, you are going to have a test.

In the

field of philosophy, testimony is defined as the intentional transfer of a

belief from one person to another. The transfer can be verbal, written, or

signaled in some way. Issues concerning the epistemology of testimony have

become increasingly discussed in contemporary philosophy, with the debate

widening out from epistemology to other fields such as philosophy of mind,

action theory, and philosophy of language.

The expression 'testimony' in everyday

usage in English is confined to reports by witnesses or by experts given in a

courtroom, or other formal setting. But in analytic philosophy the expression

is used as a label for the process by which knowledge or belief is gained from

understanding and believing the spoken or written reports of others generally,

regardless of setting. In a modern society testimony thus broadly understood is

one of the main sources of belief. Very many of an individual's beliefs are gained

second-hand: from personal communication, from all sorts of purportedly factual

books, from written records of many kinds, and from newspapers, television and

the internet. Testimony enables the diffusion of current news, information (or

misinformation), opinion and gossip throughout a community with a shared

language. It also enables the preservation and passing on of our accumulated

heritage of knowledge and belief: in history, geography, the sciences,

technology, etc. We would be almost unimaginably epistemically impoverished,

without the resources provided by testimony in its various forms.

This statement was made by Joyce Meyer. As I see it, this

statement is largely true. But sometimes we can find testimony from previous

tests. As Joyce Meyer points out here, I do not see the need to examine

yourself if you need testimony. You can get another person to check and get

testimony.

When testimony is trustingly accepted by an individual, she

acquires beliefs through it. In a modern society, very many of an individual's

beliefs are derived directly from testimony, or depend for their grounding on

other beliefs so derived. Are these beliefs derived from testimony ever

justified, and apt to be knowledge? The primary concern of philosophy regarding

testimony is epistemological: to explain the status as potentially justified

and knowledgeable.

Beliefs dependent on testimony. - Or, if the upshot is

skeptical, to show why such beliefs are not apt to be justified and

knowledgeable.

- Descriptive Local Question

- Normative Local Question

In what conditions, and with what controls, should a mature

adult hearer believe what she is told, on some particular occasion? (Fresh

instances of testimony, for an adult hearer.).

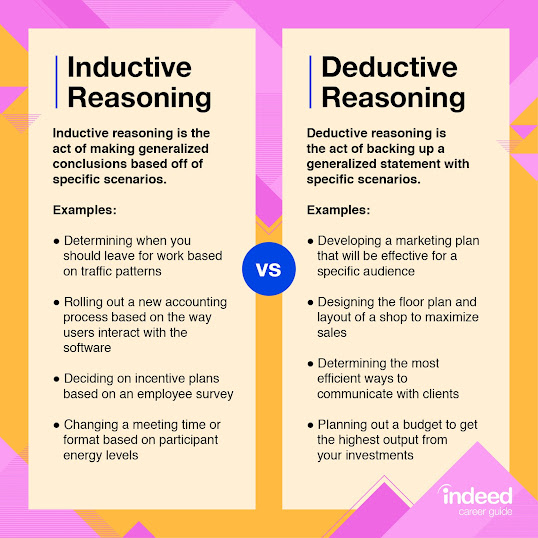

- Descriptive Global Question

What is the actual place of testimony-beliefs overall, in a

person's structure of empirical belief? What is the extent of dependence on

testimony for grounding (epistemic dependence) of our beliefs? And what is the

relation between testimony and our other sources of empirical belief:

perception, memory, and deductive and inductive inference from empirical

premises?

- Normative Global Question

How, if ever, can a system of beliefs with uneliminated

epistemic dependence on testimony be justified?

Testimony is an invaluable source of knowledge. ... This

leads to the development of a theory that gives proper credence to testimony's

epistemologically dual nature: both the speaker and the hearer must make a

positive epistemic contribution to testimonial knowledge.